Editor's Note: Today, we continue a fascinating article by Celeste Behe. Enjoy Part I here. LMH

Editor's Note: Today, we continue a fascinating article by Celeste Behe. Enjoy Part I here. LMH

The efficacy of siblings as a refining force can’t be overrated. Where Mom and Dad’s efforts at cultivating virtue have failed, the siblings in our family have succeeded. Witness this actual exchange between my optimist and my malcontent, overheard on a car trip back from Grandma’s:

O: (sigh) “I just love this.”

M: (with the hint of a sneer) “Love what?”

O: (dreamily) “Oh, you know…everything.”

M: (with a fully developed sneer) “Everything? You mean, like spinach, and headaches, and math, and bee stings, and…”

O: “No, I mean I love this. Riding in the car, and thinking about the fun visit

we had, and looking out the window at the purple sunset…”

M: “That’s not purple.” (Squinting a bit) “Well, maybe it is sort of purple. But it’s more like – what’s that color – magenta or something?”

O: “Mmm, I think so. Or I guess you could just call it pinkish-reddish-purplish.”

M: “It’s easier to call it magenta. (Pause.) Look! Serious clouds!”

O: “You mean cirrus clouds.”

M: “Well, whatever. But, yeah…it really is a nice sunset.”

Lectures on gratitude had fallen on deaf ears. Writing assignments – “In all things give thanks, for this is the will of God,” fifty times in cursive - did little more than improve his penmanship. But a few minutes spent looking through the appreciative eyes of his brother taught my son a lesson in thankfulness.

What about the mom who shows a preference for her sunset-loving boy? Or the dad who goes out of his way to spend time with his tough-guy son? How does this affect the siblings of the “favorites,” and how can parents deal with associated feelings of guilt?

“All children have different needs,” says Wendy Krisak, private practitioner and Assistant Director of Counseling at DeSales University. “Parents may need to show a little extra care to one child over another. Some research shows that many children actually understand when their parents have to treat siblings differently.” Parents who feel guilty about the disparity should reflect on the reasons for it. Says Krisak, “Parents often don't even know how much or how little time is being given to each child because it is so interrupted by daily happenings in the household.” Since the odds of having a high needs child are greater in a large family, and the sheer number of “daily happenings” can be staggering, favoritism may be harder to avoid. Recently this became an issue for Vincent, two of whose siblings had - for reasons both good and bad - been garnering most of Mom’s attention. Vincent was feeling neglected, and the usual cheering-up tactics weren’t working. So I invented a holiday which all family members were required to observe: “Vincent Appreciation Day.” The honoree was ceremoniously led to a cushy sofa, where he was given a plump pillow, a stack of “Calvin and Hobbes” comic books, a plate of snacks, and a little bell to ring to call his “subjects” (i.e. siblings) for service. Silly? Maybe so, but all the attention really did make Vincent feel loved and appreciated. An unforeseen benefit was a genuine increase in affection for Vincent from his siblings, which lingered after the “holiday” had ended. (I think of it as the “Whistle a Happy Tune” effect.)

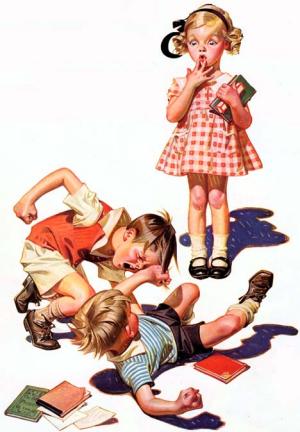

But as every parent knows, affection between siblings waxes and wanes. And when it’s on the wane, the domestic church can become a domestic combat zone. Imagine a fracas in the family room, a quarrel in the kitchen, and a brawl in the bedroom…all running concurrently. If, as clinical psychologist Dr. Ray Guarendi says, “chronic sibling quibbling” is normal, then “normalcy” in a large family can drive a parent to the brink. I used to be one of those parents. Striving to be a conscientious mother, I’d always try to get to the bottom of whatever squabble was taking place in the room in which I stood. I had to figure out “who started it,” or “who had it first,” or “who was settling the score.” Unfortunately, the final score was always the same: Squabblers, 1; Mom, 0; Tylenol, 2 Extra-Strength.

“Parents shouldn’t play detective by sorting out arguments,” says Dr. Guarendi, father of ten and author of “Discipline That Lasts a Lifetime.” “But that doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t get involved.” According to Dr. Guarendi, “Parents have been misled into thinking that siblings should be left to work out conflicts on their own.” This is a recipe for trouble, he says, and can amount to parental permission for kids to mistreat each other. Instead, “parents should set boundaries”. And it isn’t enough to draw the line at, say, kicking or punching. With limits like that, “what’s to keep them from name-calling, or worse? It is important that family members show respect toward one another. That means that the smallest snotty remark should not be permitted.”

It has been noted that large amounts of time spent exclusively in the company of one’s peers can be detrimental to a child’s social development. This tends to be less of a problem in large families, where siblings must interact on a daily basis with multiple personalities at various levels of maturity. The regular exposure to human vagaries in the formative years develops interpersonal skills that might otherwise remain dormant.

Seventeen-year-old Leo’s rather fluid personality has, I believe, been molded mainly by interaction with his siblings. When Leo is hanging with laid-back Ben, for example, he’s a carefree kid; when with erudite Grace, Leo transmogrifies into an earnest youth with Serious Ideas. In debates with Vincent, Leo can be maddeningly contrary, but he is as meek as a geek when Gerard demands to have his own way. Leo’s chameleon-like shifts in behavior – besides being lots of fun at parties – allow him to adapt easily to social situations outside the home, and help him to avoid the awkwardness that’s typical of teenagers.

Then there’s the phenomenon of de-identification, the process by which siblings differentiate themselves from one another. Take, for example, a teenage boy and his adolescent brother. Are all of the older boy’s energies directed toward “making it” as a grunge rocker? Don’t be surprised if the younger brother sets his sights on medical school. If the oldest girl in the family is a peacemaker, her 11-year-old sister may distinguish herself as a rebel.

These self-made personas can serve siblings well after they leave the nest. During my own childhood, I decided to be the calming force in my family. Admittedly, it was something of a struggle, since I too carried the genes that made my brothers so impetuous. But I still managed to acquire a measure of that blessed serenity that, three decades later, has helped me through more than a few family crises.

What really tests my “mellow mom” persona are the daily “trials and tribs of mothering sibs.” Self-doubt is one bugaboo that can make me feel like Auntie Mame, wondering whether she did a good job in raising her nephew: “Did he need a stronger hand/ Did he need a lighter touch/ Was I soft or was I tough/ Did I give enough/ Did I give too much?” In moments when my confidence falls flatter than Kansas, the Mellow Mom persona presents a cool and self-assured image to my family. I’d never have guessed that the thorny sibling relationships of my childhood would one day make me a more effectual parent!

Copyright 2011 Celeste Behe

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments