Editor's Note: Today we welcome Brittany Balke as a contributor. Brittany brings us a different Catholic perspective: she's a practicing Byzantine Catholic and plans to share more about that in the coming months. She blogs at Seeking to Be Human, so be sure to visit her there, too. Welcome, Brittany! -SR

Almost four years ago, the Lord didn’t just introduce me to my future husband; he brought me to my spiritual home in the Byzantine Catholic Church.

I grew up proudly practicing Roman Catholicism and was taught by innocently ignorant catechists that the unity of Catholicism was in the Mass. They taught me that every Catholic all over the world was celebrating the same Mass and hearing the same readings.

Imagine my surprise when, in my early twenties, my friend (a.k.a. the guy I was very interested in) invited me to a Ruthenian Byzantine Divine Liturgy for the first time.

I didn’t like it. I know there are a lot of Romans who go to a Divine Liturgy for the first time and swoon over it. I did not.

I believed it was legitimately Catholic, but I just didn’t like it. There was too much stuff going on: incense with bells, chanting the whole thing, troparia, kontakia, crossing yourself the “wrong” way all the time, and hymns to the Theotokos that made me want to call my Protestant friends and tell them they were right about us worshiping Mary.

Moreover, it radically changed my perception of Catholic unity. I realized from this first Liturgy and later ones that Byzantine Catholic spirituality was not merely cosmetically different from the Roman spirituality that I knew, but that it was a vastly different way of celebrating and understanding Truth, such as in seeing original sin as “ancestral sin” instead and with a different understanding of its effects.

Our unity, I eventually discovered, was in Jesus Christ and based on some shared doctrinal beliefs, but not necessarily in sharing every belief or in having the same liturgies. I had some difficulty dealing with all of this, but I pretended that I at least sort of liked it in order to impress the guy.

Not long after that first Divine Liturgy, I had a strange experience while napping in my backyard. Maybe it was just the heat of the sun, but I tend to believe what happened was truly mystical. Drifting out of sleep, I felt a strange nearness to God. I felt color and warmth. And something--or someone--conveyed to me without words that this friend of mine and the Byzantine Church were the keys to my spiritual well-being, that they would change my life for the better.

And that messenger was absolutely right.

Slowly but surely, liturgy by liturgy, I saw that the Ruthenian Byzantine church was my true spiritual home, and that my Roman upbringing had laid the solid spiritual foundation for me to be able to recognize the East as home. Eastern spirituality filled in the gaps that Roman spirituality had left in my heart, and, even though I did not share my husband’s Ruthenian ancestry, I found myself falling in love with the ethnic shadings of our little church.

More and more, I felt filled rather than distracted by everything going on in the Divine Liturgy. A little more than a year after that first Divine Liturgy, my “friend” and I celebrated the Mystery of Crowning and were married. A few months ago, we had our first child, and her presence in our lives both before and after birth seems to have invigorated our desire to lead better and more authentically Byzantine spiritual lives.

However, I can’t say it’s been incredibly easy to be Byzantine in a Catholic culture where we tend to be the minority. Finding resources to better understand Byzantine theology and spirituality has proven difficult.

Our churches are few, and so I often have trouble making it to as many liturgies or activities as I would like because the closest Byzantine church is 15 miles away through traffic. That distance can also be an obstacle to building community with other parishioners. So is the fact that we can be kind of a tourist attraction, filling many seats with curious Roman visitors rather than permanent Byzantines. (This isn’t to say I have any problem with Roman visitors. I was one, too, and I am grateful they are getting to know us!)

I would guess that many of the Byzantine moms out there deal with similar struggles and others, and that’s why I’m here to contribute on CatholicMom.com. I hope to build a little bit of support for us Byzantine moms. I want to share what I’ve learned so far about family life and living an Eastern spirituality as well as to hear what you’ve learned.

I want to not only be a source of wisdom, knowledge, humor, and empathy, but I want to hear your wisdom, knowledge, humor, and empathy. Many of you have been Byzantine and/or mothers for much longer than I have, and so I hope you’ll give your contributions in the comment section with each article. Of course, I hope anyone who feels they have something to add about motherhood or spirituality feels welcome to participate in discussions as well, whether you are Eastern, Roman, Oriental, or any other kind of Catholic; Orthodox; or of any other persuasion.

Speaking of discussion, here’s your first question:

What do you want me to write about? Do you have questions about Byzantine Catholicism? (My husband is getting his Master’s degree in Eastern Christian theology, so we’ll research the tough ones together.) Do you have questions about family life in the Byzantine church or just family life in general?

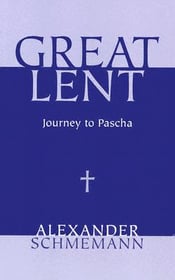

I will leave you with one of my favorite books for learning how to better enter into the spirit of Great Lent.

The book is called (no surprises here) Great Lent, by Alexander Schmemann.

Father Schmemann was an Orthodox Christian priest, and in this book, he illuminates the history and meaning behind many of our Lenten traditions and liturgies.

Now I know what some of you are thinking: this book is Orthodox, not Catholic. Byzantine Catholics are basically the Orthodox who are in union with the Pope. We differ on a couple of issues of morality and theology, but otherwise, we share the same beliefs, and I did not find any discrepancies with this book’s description of Lenten principles and our Byzantine beliefs.

Be forewarned that Father Schmemann is very honest and occasionally harsh in this book concerning his disagreement with a few Roman Catholic concepts, such as Eucharistic adoration. While I think his explanation of the discrepancies between the two theologies is both interesting and helpful for identifying true Byzantine belief, I’m not sure his implied invalidity of Roman theology is a concept those of us in union with Rome should adopt.

All of that is a very small fraction of this book, though. Mostly, you will find ways to make Great Lent more meaningful in your life. This might be the first Lent in a number of years that I have approached with excitement, and that’s because of this book.

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments