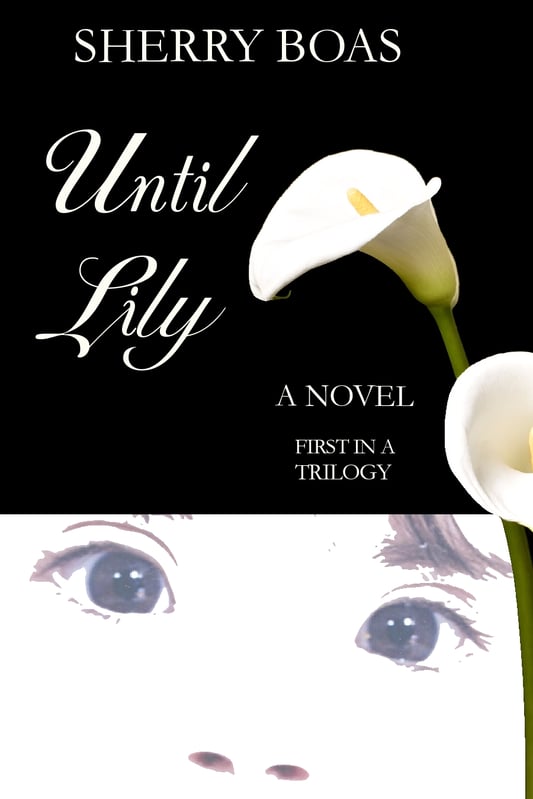

We're excited to bring this novel by CatholicMom.com contributing author Sherry Boas to our readers, one chapter at a time. Each Sunday at 9 AM Pacific, a new chapter in Until Lily will be posted. We thank Sherry for her generosity in sharing this book here and encourage you to check out the other books in the Lily series.

[tweet "Chapter 3 of 'Until Lily' by @lily_trilogy: a new chapter each Sunday! #novelgift"]

Did you miss an earlier chapter? Catch up on previous chapters before reading this one!

CHAPTER THREE

Thieves of Rainbow Whites

Mom died of breast cancer when Jen and I were in our early 30’s. Dad passed away less than two years later of a heart attack. In his time without Mom, Dad was probably the closest to me and Jen that he’d ever been. He was a good man, but he had never been warm by any stretch of the imagination. Jen and I talked about that as she lay in bed, waiting to die. Jack and I had flown out, on a sleety night-flight, to say good-bye to my sister. It was two weeks before Christmas, the children had gone to bed and Jack had gone out to the 24-hour Wal-Mart to buy presents from Jen to the kids. I lay beside Jen with the lights out. We watched the colors dance on the grey ceiling, courtesy of the twinkling lights the neighbors had strung up outside Jen’s window, in an effort to provide some small amount of cheer for her last Christmas.

“I went to this parish dance one time when I was in college, and this friend of mine was dancing with her father,” Jen said. “I couldn’t take my eyes off them. They were so happy and it looked like they must have been chatting about something funny that happened long ago. I remember blinking back tears as I watched them waltz around the floor. Right then, I vowed to marry a man like that some day. A man who'd dance with his daughter.”

“Dad wasn’t exactly the waltzing type,” I agreed.

“No, it’s far too sentimental,” she said, “and requires, not only touching, but looking into someone's eyes up close for up to three minutes.”

“Did you ever resent him?” I asked. “I mean the relationship with him?”

“I used to,” Jen said, smoothing the wrinkles out of the sheet on top her flat belly. “Then as I got older, I learned that some other daughter's fathers don’t come home at night. And some don't even claim them. And some sneak into their daughters' beds in the middle of the night and put a hand over their mouth and whisper, 'shhh’ with hot breath in their ears. So I learned to forgive an introverted, hard-shelled, unaffectionate man who never failed to grant any request within his power if it came from one of his children.”

“Especially if they professed to believe in Santa Claus,” I smiled.

Jen summoned what strength she could for a small laugh. “Yeah. Remember how we used to say we believed in Santa Claus when we were like 12 because Dad said if we stopped believing, he wouldn’t come anymore?”

“Yeah, we didn’t want that to happen.” I said. “Nope.”

The smell of laundry disinfectant wafted into my face as I adjusted the bed covers. It was an odor that couldn’t even be overcome by the live pine wreath the hospice nurse brought and hung with red velvet ribbon from the curtain rod of Jen’s bedroom window.

“What was your favorite Christmas present?” I asked Jen.

“Oh, that’s easy,” she said. “Twelve-string acoustic. 1982.”

“Oh, yeah. You never put that thing down. Much to the dismay of the rest of us who lived with you.”

“I wasn’t that bad,” Jen said, swinging her limp arm at me. Her hand landed on my bicep like a dead fish. “What about you?”

“Hmmm?”

“Your favorite Christmas present,” she said.

“Hmmm. I don’t know,” I said. “There were so many, weren’t there?”

“Do you think Dad gave us all that stuff to make up for not being able to give us anything emotionally?”

“Why wasn’t he able to?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Jen said. There was a minute or two of silence. “I’m going to see him in a few days. Want me to ask him?”

“A few days?” Where was she getting her information?

“Give or take,” she said casually.

I lay there thinking about where the conversation started and remembered that she said she wanted to marry a man who would dance with his daughter.

“Are you sad that you never married, Jen?”

“You know,” she adjusted the pillow behind her back with one hand and weakly wriggled her back into it. “I used to pray for a man who would hug me. I just had fantasies of being held. But after the children, I just never needed that anymore. I was holding them and that’s really all I needed.”

I marveled at her strength.

“Jen, are you scared to die?” I asked.

“Are you?” She turned her head toward my face and searched my eyes for truth.

“I don’t know.” That wasn’t truth.

As a kid, I used to get terribly upset when my parents went away. I would cry like I was grieving – and I was. I didn't just miss my parents. I was, at a very early age, an accomplished worrier. So if I heard a siren, I automatically assumed it was for them. My parents would always tell me before they left that they wouldn't be gone long because they knew I was heartbroken without them. But they invariably stayed out past the time they said, which made me certain they were in some horrible accident. I don't know to this day why I thought that way – how I knew to listen for sirens. But it all started after my grandfather died. Our family was staying in our grandfather's house and our parents had to go out to tend to the business of wills and such, leaving us in the care of great-aunt Barbara and other strangers. I remember a wave of panic overtaking me as I wondered if Mom and Dad would ever come back. I found momentary comfort in the realization that my mother had left her purse behind. But then again, my grandfather left everything he owned, and I knew he wasn't coming back for it. At the age of 6, I had touched his stone-cold hand as he lay in his casket and realized death was final. The next day, with distant relatives serving up casseroles and Texas sheet cake at my grandfather’s duplex, I cried after my parents for the first time. The tears mixed with the music the neighbor downstairs was playing made me queasy and dizzy. "Don't rock the boat, baby. Don't tip the boat over." To this day, I hate that song. Not that there’s much danger of hearing it anymore. I hate foil-wrapped chocolate too because one time before my parents went out to a Christmas party, they gave me a bag of Brach’s chocolate bells. My mother explained that they would be back before I knew it. I sat there unwrapping, bell by bell, popping them in my mouth, hoping the sweets would make me feel close to my mother. The more I ate, the farther away my parents felt, until finally, I had binged myself into a nauseated hysteria, listening to the scream of faraway sirens.

Jen’s Christmas lights flickered off for several seconds and then resumed their oblivious twinkling.

“You’re going to die too, you know,” Jen said, taking my hand into her soft, cold grasp. “Maybe even before me.”

I wrinkled my brow, trying to follow her logic.

“All those high-cholesterol comfort casseroles people keep bringing,” she said. “Deadly.”

“Yeah,” I said with a slight smile, which I didn’t feel like forming. A long silence followed, with Jen’s hand in mine or mine in hers, until I wondered if she had fallen asleep.

“Jen,” I whispered. “Uh-huh?”

“I guess I am scared to die.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know,” I said, squeezing her hand. “I guess I’m afraid of a big black nothingness. Like kids are afraid of the dark.”

“But it’s not dark,” she said. “It’s not nothingness.” “What is it?”

“I’m not sure – exactly.” she studied the ceiling and then looked back into my eyes. “Want me to send you a postcard when I get there?”

I let out a small laugh. “So, you’re not afraid? At all?”

“I’m afraid of what’s going to happen here when I’m gone.”

On Christmas Eve, Jen asked Jack and me to take the children to Mass, which was their family custom. Before we left, Jen took my hand in hers.

“Bev,” she said. “Please pray for an answer.”

“An answer?”

“About what to do with the kids, Bev.” Her eyes were sunken and pleading.

“OK, Jen.” I kissed her on the forehead. She closed her eyes and managed a slight smile. Well, I hadn’t been much in contact with God, and I didn’t exactly know how to start a conversation now. During Mass, I just sat there thinking about how much I was going to miss Jen. She was the only living record of my childhood. After she goes, there will be no one else to say “remember that time we found Mom sitting in the driver’s seat of the car in the garage with her suitcase and cosmetic bag, and when we asked her what she was doing she said she was pretending to go on vacation?” Or “remember when Mom got so mad at us for fighting over sugary cereal that she grabbed the Cap’n Crunch and poured it all down the garbage disposal?” Or “remember when we used to wait for Dad to sit down in front of the TV after dinner so we could steal his wintergreen Lifesavers?” I was deep in thought about us rummaging through his brief case and coat pockets looking for those Lifesavers, which, for some strange reason, we called “rainbow whites.” A ringing bell, signaling the Consecration, brought me back to my pew and I looked over at the children. Lily had her head lying in Terry’s lap and Terry was stroking her hair. On the other side of Lily was Jimmy whose arm was outstretched, resting on her leg, fingers intertwined with hers. It was then I had one of the most lucid moments of my life. And it was nauseating. These three children were about to lose their only parent, and there was no way I was going to let them lose anything else. They had to stay together. Someone was going to have to take all three. Please God, don’t let it be me. Was I actually praying?

When we returned from Mass the hospice nurse informed us my baby sister was gone.

I will forever grieve the fact that Jen died with the most important thing in her life unsettled. The last thing I had told her about the future of her children is that I might be able to take Terry and Jimmy. But probably not Lily. I knew we could find a good place for Lily, though, because I had gone on-line and found a website for parents wanting to adopt children with Down syndrome. I couldn’t believe it. Having a disabled child born to you and learning to accept the hand dealt you is one thing. Signing up for trouble is quite another. The fact that there were so many people willing to do this was both comforting and mystifying. But I know it broke Jen’s heart to think of her children being split up. I was going to tell her when I returned from Christmas Eve Mass that the thought had broken mine too, but I never got a chance to.

People at the funeral were abundantly kind. As her closest living relative, I was the fortunate receptacle for all the Jen stories people had a need to tell. So many people talked about her generosity. A long line of friends and coworkers streamed by her coffin to say goodbye.

I hate to admit it, but throughout the whole thing, I nursed a secret hope that one of the mourners would introduce himself as Lily’s father and beg for custody. Maybe he’d even ask to raise all three children, desiring they be kept together for his daughter’s sake. No such man ever surfaced, but the idea of him spans our lives like a phantom burning some kind of indelible mark on our future. Despite the potency of his potential presence, I have grown adept at putting him off. I’ve done it, in fact, for three decades, half hopeful and half petrified to find him dead by the time I should decide to break my promise and fulfill Lily’s request to track him down.

Jen’s funeral was probably hardest of all on Lily. I led her by the hand to her mother’s side and lifted her up. She looked at her mother and back at me, put her forefinger to her lips and said “shhhhhh.” At my prompting, she gently laid a rose on Jen’s chest with the other two from Terry and Jimmy. As I started to walk away, Lily stretched out her hands toward her mother and whispered, “Mama.” I took her back and she leaned in to give Jen a kiss. Then she put her hand on her mother’s shoulder and shook it gently, trying to wake her.

“Let’s go, Honey,” I said.

“Dow-” she demanded, pointing to the floor.

I put her down and she stood in front of the coffin, looking out at the rest of the room. I told her it was time to go sit down now and give other people a turn to say good-bye to her mother. She said no. I took her by the hand and she slipped her hand back out of mine and planted her bottom on the floor.

“No,” she whispered.

Terry noticed what was happening and came to talk her into moving. Lily just shook her head and put her head in her hands. I finally just scooped her up in my arms, and she let out a loud cry, like a baby who is hungry, as I carried her away. Jimmy came rushing over from his seat, where he had been sitting with his elbows propped on his knees and his chin in his hands.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“She wants to stay with Mama,” Terry whispered.

Jimmy put his hand on Lily’s back. “It’s OK, Lily,” he told her. “We’ll see Mama later.”

“Jimmy, Honey, we really should tell Lily the truth about your mother,” I whispered. “So she can come to accept it.” I had read several books on the topic since I found out Jen was dying.

“I am telling her the truth.” Jimmy had eyes the color of the pond adjacent to our backyard where we grew up in Wisconsin. “We’ll see her later in Heaven.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if Jimmy were right, I thought. I missed my sister already, and the thought of never seeing her again was unbearable. What if all my sister’s beliefs were not just crutches or superstitions? What if she was experiencing joy beyond measure right this very moment? What if she were kissing the face of God?

I once heard a man, in describing his near-death experience, talk about Heaven as a release from all the emotional and physical pain he didn’t even know he had. He said we all go around in this state of suffering, but don’t realize it because we have become so accustomed to it – like people who live for years with backaches. Heaven, he said, relieves all the disregarded pain we unknowingly endure during our imperfect existence on Earth. There were moments in the years to come when I came to realize how this could be so. Before the children came along, if you would have asked me if the glass was half empty or half full, I would have said “Who cares? I’m not thirsty anyway.”

Today, I will tell you the glass is filled to the brim and I would give anything for a sip.

Join us next Sunday for the next chapter!

Background image via

Pexels, CC0 Public Domain.

Background image via

Pexels, CC0 Public Domain.

Buy this book through our Amazon link and support CatholicMom.com with your purchase!

Be sure to check out our Book Notes archive.

Copyright 2017 Sherry Boas

About the Author

Sherry Boas

Sherry Boas is author of the Lily Series, which has grown into a beloved collection of novels whose characters’ lives are unpredictably transformed by a woman with Down syndrome. The former newspaper reporter and special needs adoptive mother of four is also author of A Mother's Bouquet: Rosary Meditations for Moms, Billowtail, Victoria's Sparrows, Little Maximus Myers, Archangela's Horse, and Wing Tip. She runs Caritas Press from her home office in stolen moments between over-cooking the pasta and forgetting to dust the chandelier. Find her work at CaritasPress.org.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments