April 1 was Easter Day. It isn’t a coincidence, I think, that April is also denoted as Autism Awareness Month. Do you know how many times I’ve begged and pleaded with God? How many times I’ve leaned into the promise that He makes all things new?

Autism awareness isn’t for those who trudge uphill, carrying the cross of autism. It isn’t even for the Simons (parents and caregivers) who help bear the wood of this unique, splintered, heavy, journey. Autistic souls, and those who love them, are very aware. Trust me.

Before 1990, the odds that a baby would be autistic were 1 in 10,000. After that year, the rates exploded. I believe the reason is environmental. That is another discussion. Lately, I hear that we’ve reached odds that 1 in 43 babies will be diagnosed as suffering with some level of autism. Hmmm, doesn’t seem so odd ... or should I say rare? I also heard that if we continue this trajectory that by 2032, 1 in every 2 babies will be autistic. What?!!!

I know something will break through. It can’t continue this way.

We are at a new level of autism awareness. Autism has grown up. Literally. Babies born in the '90s are in their twenties now. After age 21, the usual services stop. Thankfully, pushing is coming to shoving, and because everyone now knows or is related to someone who has autism, society is being forced to be aware. Opportunities for education, employment, and social life are budding.

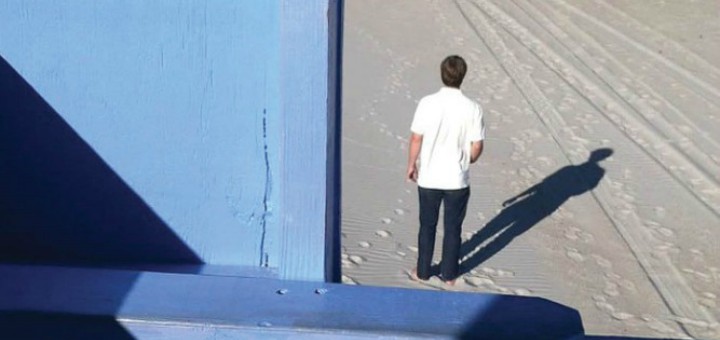

My son was born in 1990. He is now 28. My husband and I are Paul’s legal guardians. Paul does well athletically. He’s an elite runner. He places in the top ten of local 10-Ks and half-marathons. He’s a beast when it comes to assembling card games at our family business. Also, nobody gets the dishes cleaner than Paul at our neighborhood Mexican restaurant. His challenges are social and cognitive.

I have written a book called Paul’s Prayers, published by Good Books publishing. You can order it through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your favorite independent bookstore. The following is an excerpt from the chapter called “Guardian Angels Can Fly.”

I have written a book called Paul’s Prayers, published by Good Books publishing. You can order it through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your favorite independent bookstore. The following is an excerpt from the chapter called “Guardian Angels Can Fly.”

Copyright 2018 Susan Anderson

I have written a book called Paul’s Prayers, published by Good Books publishing. You can order it through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your favorite independent bookstore. The following is an excerpt from the chapter called “Guardian Angels Can Fly.”

I have written a book called Paul’s Prayers, published by Good Books publishing. You can order it through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your favorite independent bookstore. The following is an excerpt from the chapter called “Guardian Angels Can Fly.”

It was a hot day in July. My husband was out of town working. It’s always interesting when he’s gone. Something usually breaks, like an appliance. Once it was the water heater, another time the dryer, and twice it was the washing machine. By the fourth washing machine in sixteen years, I started naming them. I figured that if I personified this metal machine slave that I expected so much from, maybe it would build in some longevity, some loyalty. The latest washer’s name is “Bubbles.” I was also a full-time caregiver for my totally blind eighty-seven-year-old mother-in-law. She was bedridden and relied on me for everything: meds, getting dressed, meals, showering and grooming, clicking up her electric blanket, sending emails to her friends, reading classics aloud. It was, as my husband says, “a real program.” For much of this book, she also served as my “blind editor.” She taught me a lot about getting to the point and staying on point with writing. For a year and a half, writing this book, seeing to Paul, and taking care of Mom was my full-time job. On this particular day, Paul decided to mow the grass. He was twenty-five at the time. Up to that point, we always had one of our other kids on this chore. First Scott, then Mark, then Danika, then Katie. Paul avoided the sound of the mower, with good reason. Motorized objects were a scary proposition for us with Paul. We were also busy with many other things, so it was easiest to expect our other children to do their fair share of work around the house. We believed that they each needed a certain amount of responsibility for their teenage development. Then they all, one by one, started leaving the nest. It was a brand-spanking-new lawn mower. We don’t use a side bag to catch lawn clippings. In North Carolina, the summers can be pretty humid. This, along with a lot of rain, causes the grass to clump and clog the underside of the mower. Often the mower cuts off. Then you have to roll the thing over to the cement and tap it up and down to loosen the muck, dropping it off on the driveway. This is exaggerated if the grass has grown too high. Also, with Paul, most everything is exaggerated. He would run the mower, zigzag, from one corner of the square yard diagonally to the other, cut the mower off, roll it to the driveway, tap, tap, tap—actually, bang, bang, bang—and then start it up again. In a way, it’s hysterically funny to watch him mow the grass. He bops along, wagging his head back and forth, shoulder to shoulder, sort of hopping up and down, and zigzagging all over the yard, like a Dr. Seuss pattern. He uses the mower like most people run a vacuum cleaner. I was in the garage repotting some plants and keeping an eye on him. Paul was cutting out the mower every few swipes and I became concerned that he’d break the thing. I approached him, saying, “Paul, you can’t keep turning off the engine. You might break it. That’s a new mower.” Then he got mad. Paul being mad just makes things worse. He becomes defensive and jerks his arms and legs around, making zinging noises. Also, rather than correcting the problem, he’ll do the exact opposite of what I’m commanding or suggesting. He had a hard time with constructive criticism and didn’t receive it well. He cranked the mower again. He walked fast over the yard, taking large steps, rigid in posture, jerking his head around, agitated. Then he cut the mower again. As the end of my own rope, frayed and unraveled, I barked. “Paul, do ya want to break it? That’s a new mower. If it breaks, are you going to buy Dad a new one? I mean, do you want to help or not?” Paul yelled back, “Only if you don’t act like Dad!” At wit’s end, I said, “Oh, trying to teach you how to do it?” “Yeah,” he yelled. “Okay, well, don’t cut your foot off. I don’t feel like going to the emergency room today!” I walked away. Back in the garage, I skipped the garden gloves, reaching my bare hands into the black soil, wanting something grounding, earthy, to calm my soul. I liked the smell, the feel of the dirt. I wished everything was that basic. All the sudden, I thought to talk to Paul’s guardian angel. Not growing up Catholic, the angels and saints have been an acquired bonus to my relationship with God and his family, his kingdom. It felt unnatural to pray this way. But when it comes to my Paul, I’ll try anything. “Paul’s Guardian Angel, I humbly ask that you speak to him, because I can’t get through to him. Thank you.” It was rather robotic, my words coming out of my mouth. I wasn’t even sure I believed. But then everything changed, and it started with me. I went about my business of digging and planting, holding the root ball steady within the center of the pot with my left hand, scooping with the other hand, mounds of soil in and around the plant, pushing the soil down firmly, with tender care. I didn’t check on Paul after that. My psychology totally changed. I settled down. I moved the plants back into the house and checked on Granny. After a while, Paul came in, his face relaxed. He was totally changed too. His demeanor was calm. He looked me in the eye and said, “Mom, can you come look at the grass and tell me if I did a good enough job?” The lawn was perfect. That’s when I realized that angels have wings. After that, I started contemplating memories in my own life when an angel might have had an influence on a good outcome. I wondered how many times I’d been rescued. I thought of my littles, romping around outside and in the house, and carting them around in the car. What would we do without angels? I began to call upon my guardian angel. Catholic teaching says that angels are super intelligent, but they aren’t like we humans. Stretching your wings is always a good thing, as long as your feet are firmly planted on the ground. With autism being the looming reality, there is not a concern there. Why not reach for the heavens when it comes to my Paul?

Copyright 2018 Susan Anderson

About the Author

Susan Anderson

Susan Anderson is a wife and mother of six. Becoming Catholic at age 33, she is an avid fan of Mary and keeps her sanity through rosary prayer. She helps Rob, her husband, at Cactus Game Design, provider of Bible based games and toys. Her book, Paul’s Prayers, is about her oldest autistic son, which will be published March 6, 2018. To pre-order: http://goodbooks.com/titles/13642-9781680993479-pauls-prayers Her website: www.SusanAndersonwrites.com

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments