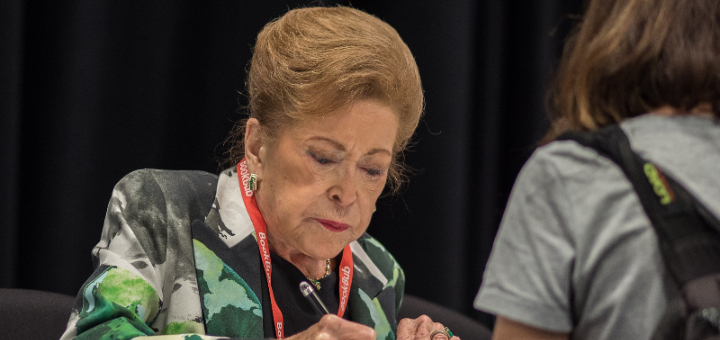

Rhododendrites [CC BY-SA][/caption]In my writing area I keep a framed picture of Mary Higgins Clark that shows her sitting at her typewriter at her kitchen table, working on one of her early novels.

Well, that makes it sound rather more grand than the reality is. My “writing area” is a shelf in the dining-room hutch, mostly filled with tablecloths, but also containing the Mary Higgins Clark photo, some pens and highlighters, and an untidy calendar bulging with random notes. And the “framed photo” is a 2x3-inch black-and-white picture clipped out of the back of Clark’s wonderful memoir Kitchen Privileges, taped to a piece of card stock, and put in an old 5 x7 frame repurposed from a kid’s craft.

But the location of the shelf is handy as it happens to be situated in near proximity to the dining-room table, where the actual writing takes place, alongside many other activities: homework, games, crafts, Lego construction, even meals!

Our dining-room table is a very busy place.

And when writing gets its turn at that table, Mary Higgins Clark is right there keeping watch. I think she’d approve, since she got her start as a novelist at her own kitchen table. And her “writing area” was the floor in a corner of the kitchen where she kept her typewriter.

She did her writing between 5 AM and 6:45 AM. At 6:45 she put her typewriter back on the floor in the corner to wake her five kids, about whom she wrote:

Rhododendrites [CC BY-SA][/caption]In my writing area I keep a framed picture of Mary Higgins Clark that shows her sitting at her typewriter at her kitchen table, working on one of her early novels.

Well, that makes it sound rather more grand than the reality is. My “writing area” is a shelf in the dining-room hutch, mostly filled with tablecloths, but also containing the Mary Higgins Clark photo, some pens and highlighters, and an untidy calendar bulging with random notes. And the “framed photo” is a 2x3-inch black-and-white picture clipped out of the back of Clark’s wonderful memoir Kitchen Privileges, taped to a piece of card stock, and put in an old 5 x7 frame repurposed from a kid’s craft.

But the location of the shelf is handy as it happens to be situated in near proximity to the dining-room table, where the actual writing takes place, alongside many other activities: homework, games, crafts, Lego construction, even meals!

Our dining-room table is a very busy place.

And when writing gets its turn at that table, Mary Higgins Clark is right there keeping watch. I think she’d approve, since she got her start as a novelist at her own kitchen table. And her “writing area” was the floor in a corner of the kitchen where she kept her typewriter.

She did her writing between 5 AM and 6:45 AM. At 6:45 she put her typewriter back on the floor in the corner to wake her five kids, about whom she wrote:

I clearly remember the first time each one of my children was put in my arms — five absolutely magical moments when I felt I had touched the wondrous hand of God. (Kitchen Privileges, p. 93)Once her children were up she made breakfast, got everyone ready for school and saw them off, then dashed out the door to her job. It was a grueling routine, and she was always tired. But Clark’s beloved husband had died, leaving Clark a widow with five children aged five to thirteen. So she went to work to support her family. It didn’t help that her job was stressful, her boss difficult. Her widowhood was much like her childhood had been. Her own father died in 1939 when she was just ten, leaving her mother with three children aged seven to 12 to care for. They all pulled together and did their best to maintain themselves financially, pitching in with babysitting and paper routes and whatever else they could, but it wasn’t enough, and they lost their home. She had to forego college to go out and earn a living. Then they lost Clark’s older brother who enlisted in the Navy and died during World War II. Tragedies struck Clark’s life time and again. In the midst of them, she prayed. Throughout Kitchen Privileges she talks about her constant prayer over matters large and small. One of the moist poignant passages described her first learning of the medical condition that would eventually claim the life of her husband:

[After seeing the doctor on] the way home, I stopped at church, where I prayed, “Please let him live.” The answer I heard was, “Come, take up your cross and follow Me.” (Kitchen Privileges, p. 110)It wasn’t many more years before her husband succumbed to his heart condition. She recounted of the day in 1964 when he died:

When the children went to bed, I sat in the tall fireside chair ... I was beyond tears. For the moment, they had all been shed. This is the rest of my life, I thought. I knew the children would miss Warr [her husband, Warren Clark]. My heart ached for them. I knew about all the birthdays and holidays and graduations when they would see other kids with their fathers. I knew because I had been there. ... At home, I was going to have to assume the role of both parents. And as my mother hadn’t taken my father’s death out on us, I resolved I wouldn’t take my grief out on my children. As best I could, I would try to give them a happy home. (Kitchen Privileges, pp. 116-117, 124)She wrote that daily Mass helped her through those trying days. She got a job, started her morning writing routine, and kept at it for years. In 1969, five years after her husband’s death, her first book was published. In terms of sales, it was a dud. As she quipped, “it remained one of the great secrets of 1969” (Kitchen Privileges, p. 176). Her mother died, her job deteriorated and she ended up leaving and starting her own business. She started back to school to get her college degree. She was broke and exhausted, but she continued praying and continued writing, hoping the next book would be her deliverance. The next book was written, sent to her agent, sold, and on she pushed to the one after that. It too was written and submitted, and it turned out to be the one. As Clark was leaving work one evening in 1977 on the way to her night classes at a college in the city, she received a call from her agent telling her an offer had been received for her third book: an offer of one million dollars. Clark told her agent to call back and say yes before they changed their minds! She didn’t get much out of her class that night. Instead she kept writing “One Million Dollars” over and over again in her notebook. Driving home, her old car, which she said “for weeks I’d been nursing ... along, my fingers crossed that it wouldn’t break down,” lost it’s tailpipe and muffler (Kitchen Privileges, p. 204). The next day, she bought a new Cadillac. She went on to write 51 books. She also earned her college degree, and in time became a grandmother to seventeen. When I saw the news report that Mary Higgins Clark died on January 31, 2020 at the age of 92, I went to my dining room hutch to look at my faded photo clipping of her at her typewriter at her old kitchen table and thought, what a life of perseverance and faith. Circumstances were never as she would have wished, but she always trusted God, put her faith in Him, was open to His plan, and followed where He led. She didn’t wallow or wail. Instead of seeing only obstacles she sought solutions. And she did it with grace and joy. I’ll keep her picture in its place in the dining room to watch over all the activities that take place there, and all the activity doers, large and small, who gather there to work out their own dreams. I hope my kids glance at it occasionally and think about why it’s there. She’s a great role model for everyone who comes to our table, scribblers and non-scribblers alike. And if you think of it, offer a prayer or a Mass for Mary Higgins Clark. May eternal light shine upon her!

Copyright 2020 Jake Frost

About the Author

Jake Frost

Jake Frost is a husband, father of five, attorney, and author of seven books, including the fantasy novel The Light of Caliburn (winner of an honorable mention from the Catholic Media Association), collections of humorous family stories ( Catholic Dad and Catholic Dad 2), poetry (most recently the award winning Wings Upon the Unseen Gust), and a children’s book he also illustrated, The Happy Jar.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments