Roxane Salonen interviews the directors of a new documentary on Flannery O'Connor in light of a recent controversy.

There is nothing like being pleased with your own efforts – and this is the best stage – before it is published and begins to be misunderstood. (Flannery O’Connor, The Habit of Being)

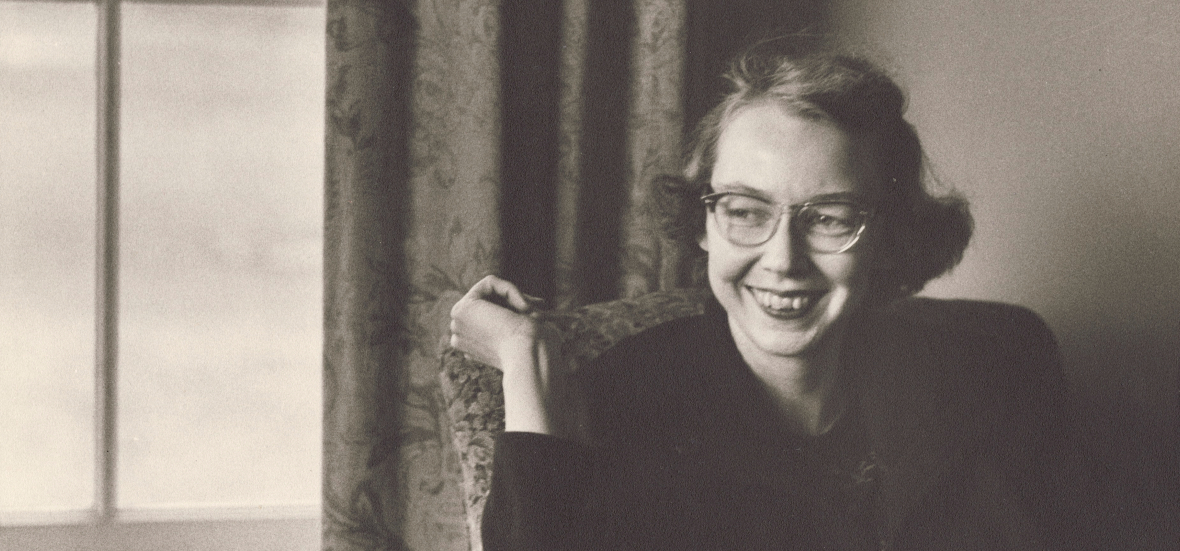

Along with knowing, from an early age, that she was dying, Flannery O’Connor was persistently afflicted with another malady: being misunderstood.

It was part of what the American short story writer and novelist endured as an Irish Catholic growing up in the Southern, Protestant Bible Belt; part of being the daughter of a mother who preferred seeing her only child a proper Southern Belle rather than an acclaimed writer; and woven within the earliest critiques of her work.

Now, the misunderstanding continues fresh, well beyond the grave, as a university dormitory previously named for O’Connor changes its name – seemingly a reaction to a June 2020 article in the New Yorker which suggests that O’Connor was racist.

In 1964 at the age of 39, Flannery succumbed to the disease of lupus – the same affliction that claimed her father’s life when she was 15 – at the peak of her career and the American Civil Rights awakening.

Many who’ve thoughtfully studied her life understand the trajectory she was on in recognizing the dignity of the human person in everyone. They realize, too, that despite her surroundings, and sentiments shared in her own home, as she grew into maturity, far from promoting racism, O’Connor was trying to expose it.

Recent conversations with the writers-directors of the new documentary about her life, “Flannery” – including an exclusive interview hosted by Endow and a personal interview – helped put the recent controversy of O’Connor in proper context for me.

Elizabeth Coffman and Fr. Mark Bosco, S.J., were eager to dispel the notion that O’Connor was racist, with Bosco stating that it’s unfair to any artist, and “absolutely unjust when it comes to Flannery O’Connor,” to label her as such, adding that, in these polarized times, “with these click-bait kinds of moments,” it’s easy to do, but wrong.

“We’re so prone to signing up for petitions without knowing anything beyond the superficial level (of the topic),” he said, “and all of a sudden…what’s a very complicated and humanizing moment in an artist’s life gets reduced down to a simple statement.”

Bosco challenged those who love art, and artists, to pause when confronted with this kind of scenario, urging them to slow down and ask questions, like, “What does the work show?” and “How does the work express what’s adequate to the human spirit?”

Human life, he said, is complex, bringing together “the dramas and the anxiousness” along with “the joys and redemption,” and all must be considered and seen in light of the whole.

O’Connor, he explained, grew up with a mother who used the “n-word” as part of daily conversation. “It was in the home, always mannered, never said to people outside,” he said. In communicating with her mother, she did, on occasion, echo it back. “Keep in mind,” he noted, “this was 1925, 1930, rural Georgia, and part of the air she breathed.”

But in time, he said, O’Connor began “interrogating that white assumption,” and her artwork “continually turns its attention to those presumptions.”

In the end, O’Connor “deconstructs” quite well the racist attitudes she’d grown up with, he said. Yet, now “she’s been canceled because of all that’s been clouded and swept aside, with quick kinds of checkmate games by intellectuals, as well as the media.”

Coffman said the contention that O’Connor was racist is, first of all, coming from “a white privileged position.” She called it a fundamental error in understanding O’Connor and her work, as well as a diversion. Real tragedies that have been unfolding – the pandemic and events surrounding racism – deserve our attention, she said, but pitting O’Connor as an antagonist here is a distraction.

When O’Connor was on a bus leaving Georgia for college, she recounted, the bus driver made a racist comment to the Black people to get to the back. “Flannery wrote, ‘At that moment, I became an integrationist.’”

And one of her first short stories, “The Geranium,” concerns a racial conflict. “It’s about the white racism that a southerner, displaced to New York, feels when a Black neighbor moves across the hall,” Coffman said. “She was writing that when she was 22, directly trying to address the bad feelings, the racism, that people have, and wondering where that came from.”

Coffman said O’Connor did this throughout her life, including “while dying in her hospital bed,” and that she was shocked to read about the controversy erupting on O’Connor surrounding this topic.

“The more research I’ve done since … the more I’ve found (evidence to confirm this),” Coffman said, adding that there’s one person who would be notably unconcerned about a college dorm being renamed due to such a controversy – Flannery O’Connor herself. “Her work is so strong. Her work will outlive this.”

Bosco brought a theological dimension to the conversation, saying that O’Conner “understood racism as an original sin,” and “indicted herself, as a good Catholic girl, confessing…that she’s been woven into that racism because of where she lives.”

Flannery was “trying to unweave it, almost extricate herself” from racism, he said, and in following her writings, we can see her “growing in her understanding, and that her faith actually has always been the horizon where her eyes are looking.”

The “Flannery” film, released in Oct. 2019, received the first-ever Library of Congress/Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film, and can still be viewed for a limited time at FlanneryFilm.com, and in a shorter version through PBS stations in early 2021.

Roxane Salonen visited Andalusia Farm in Milledgeville, Ga., home of Flannery O'Connor, in the summer of 2014, with two Catholic writer friends and wrote additionally about this issue recently for her city's daily newspaper here. Photo copyright Roxane Salonen.

Copyright 2020 Roxane Salonen

Images (unless otherwise noted): Courtesy of 'Flannery.' All rights reserved. Animation by Heidi Kumao.

About the Author

Roxane Salonen

Roxane B. Salonen, Fargo, North Dakota (“You betcha!”), is a wife and mother of a literal, mostly-grown handful, an award-winning children’s author and freelance writer, and a radio host, speaker, and podcaster (“ Matters of Soul Importance”). Roxane co-authored “ What Would Monica Do?” to bring hope to those bearing an all-too-common cross. Her diocesan column, “ Sidewalk Stories,” shares insights from her prolife sidewalk ministry. Visit RoxaneSalonen.com

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments