Taryn DeLong reviews a new biography of Sigrid Undset, a mother, Catholic convert, and author of Kristin Lavransdatter.

When writer Sigrid Undset converted to Catholicism in 1924, it was a scandal in her home country of Norway. Having read her beloved trilogy Kristin Lavransdatter, published between 1920 and 1922, though, I don’t really know why people were surprised. It is beautifully Catholic, and the first time I read it, I wondered how much the writing of it was part of her conversion. Did she write herself into Catholicism, or were the seeds planted before then?

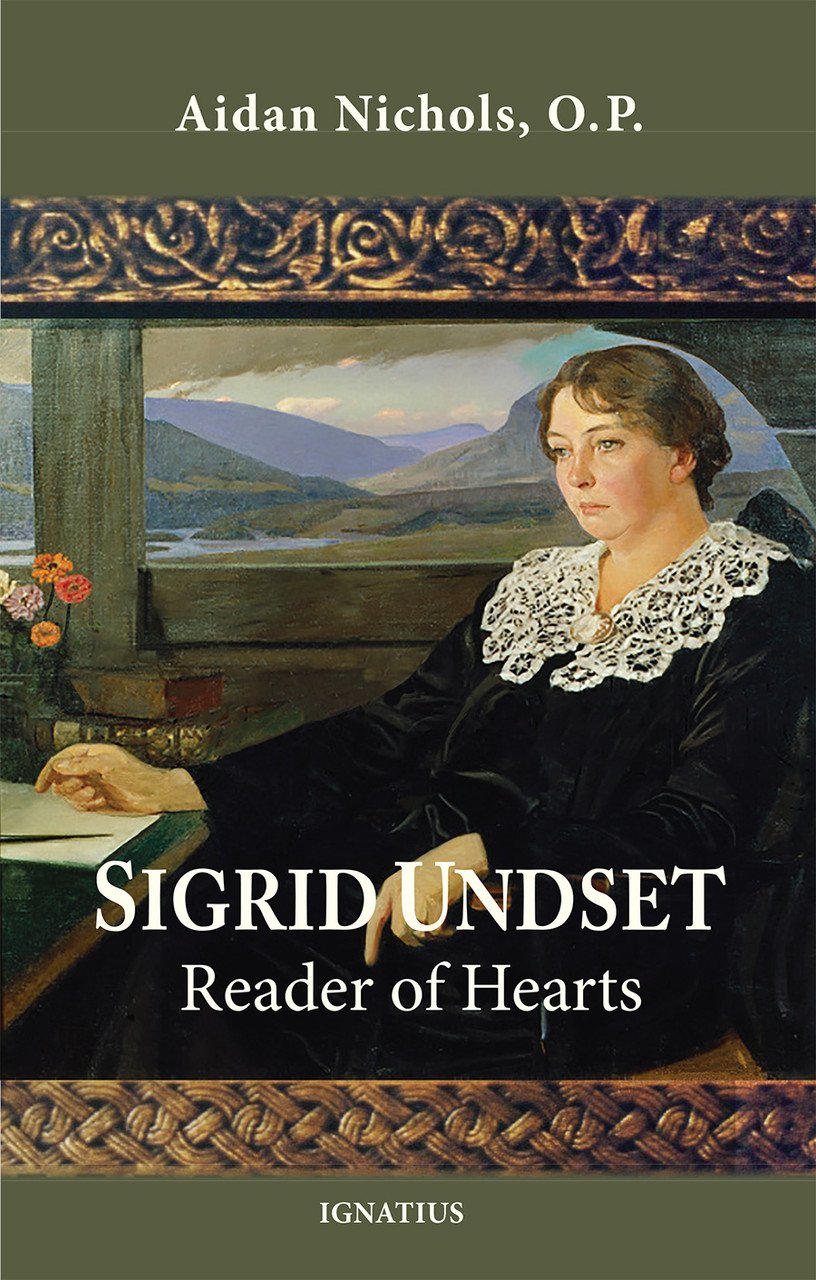

A new biography, Sigrid Undset: Reader of Hearts, explores this question. Published by Ignatius Press, it’s written by Father Aidan Nichols, a Dominican friar and former lecturer at Cambridge and Oxford. The biography dives into Undset's intellectual formation, her conversion, and the themes she explores in her writing.

I found the most fascinating chapters to be on Undset’s writing and speaking before her conversion. They held hints of where the Holy Spirit seems to have been leading her. Most interesting to me was the way she thought about women and the feminist movement. Like the Church, she opposed contraception, and she wrote that a woman “cannot achieve anything better than being a good mother and nothing worse than being a bad mother.”

Undset agreed with feminists that mothers can have interests and purpose outside the home. However, she took issue with “the frequently encountered feminist conviction that working in and for the home was, in past times, patriarchally imposed drudgery,” writes Father Nichols. She placed great value on motherhood and homemaking and demonstrated in her own life that a mother could also have a tremendously successful career (even winning the Nobel Prize for literature). She wrote prior to her conversion that Christianity “has given to women the most honorable position they have as yet been assigned.” And, reminiscent of the future Pope St. John Paul II, she viewed motherhood not only as a physical reality but as “a moral and intellectual outlook,” writes Father Nichols.

Before her conversion, Undset had an affair with a married man, whom she married after he divorced his wife. Their marriage was annulled after they had three children together. Two of her children died before Undset did; one was severely disabled, and the other was killed in action in World War II. Her depiction of motherhood in Kristin Lavransdatter is beautiful and complicated, just as motherhood is. I imagine she must have drawn on her own experiences, but this biography does not go into much detail about Undset as a mother.

Father Nichols does make it easy to see how a secular Norwegian woman, raised by agnostics in a traditionally Lutheran country, could become Catholic. He shows the shifts in her thinking that made her arrive at the conclusion,

Though it requires the grace of God—that ‘mystical and supernatural power the theologians call Grace’—finding in Jesus Christ the way, the truth, and the life, with the Church as his representative, answers to a radical, indeed inescapable, human need.

The biography also touches on the impact World War II had on Undset, in addition to causing her to lose one of her sons. Her books had been banned in Nazi Germany due to her speaking out against Nazism and anti-Semitism. When the Nazis invaded Norway, she and her younger son fled to the United States. The Nazis took over her home and used it as officers’ quarters. While in the U.S., Undset spoke and wrote to advocate for action against the Nazis. She also befriended other activists and authors, including Dorothy Day (now a Servant of God).

Upon finishing Sigrid Undset: Reader of Hearts, I have a better understanding of the beliefs and intellectual development of Sigrid Undset. I still want to learn more about who she was as a wife and mother, but for those interested in philosophy and literature, Father Nichols’ biography is well worth the read.

Copyright 2022 Taryn M. DeLong

Images: Harald Slott-Møller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; Canva

About the Author

Taryn DeLong

Taryn DeLong is a full-time homemaker who lives outside Raleigh, NC with her husband and their little girls. She is also co-president of Catholic Women in Business and co-author of Holy Ambition: Thriving as a Catholic Woman at Work and at Home(Ave Maria Press, 2024). Follow her on LinkedIn or Instagram.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments