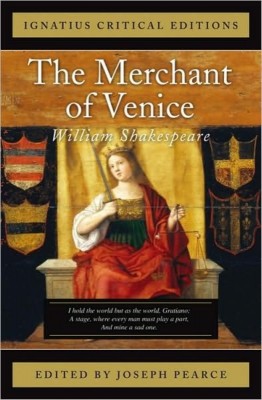

I picked up the shiny Ignatius Press Critical Edition of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice that my husband had ordered for his summer book club at our diocesan center. The cover was a beauty with its Renaissance painting of Justice. But, wait, what was this on this on the back? Just as beautiful as the cover was a description of the scope and aim of this critical edition series:

I picked up the shiny Ignatius Press Critical Edition of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice that my husband had ordered for his summer book club at our diocesan center. The cover was a beauty with its Renaissance painting of Justice. But, wait, what was this on this on the back? Just as beautiful as the cover was a description of the scope and aim of this critical edition series:

“The Ignatius Critical Editions series represents a tradition-orientated approach to reading the Classics of world literature.”—Tradition-orientated approach, I thought, I’ve never heard such a thing in all my B.A., or, rather, my Bachelor of Anti-Art—“While many modern critical editions have succumbed to the fads of modernism and post-modernism”—Memories of my college English classes came to mind, which had all been drenched in the sadness and despair of this kind of bleak, weak literary analysis.—“this series concentrates on critical examinations informed by our Judeo-Christian heritage as passed down through the ages—the same heritage that provided the crucible in which the great authors formed these classic works.”

I cheered. I did a fist pump and a little victory dance because here in my hand was a beautiful, erudite Catholic response based on reason, fact, and history—one that I never could have hoped to have given in class, but one which I had felt deep in my soul, even back then, must exist—to all of my college English professors who also chose to portray the classics in a post-modern, feminist, nihilistic “light”. After all those dark, depressing lectures that had left us in the seats—we who so needed something beautiful and challenging to aspire to, something true to ruminate upon—with the conviction that, indeed, there was no higher truth than our own opinion, nothing more to reach for than simply laughing at the irony of the world, here it was—vindication.

How I wished I could go back to class—perhaps poorly disguised in my old stretch pants and Uggs—book in hand, and stop the professor after he’d painted Portia, the obedient heroine of The Merchant of Venice who honors her father’s will by accepting in marriage the suitor who can correctly pick the casket in which her picture lay, as a victim of the patriarchical structures and gender stereotypes of the day.

I’d pull down my glasses, clear my throat, and say, “Do you think it’s possible, Professor, that instead of languishing as a helpless victim of society, Portia here is instead freely and valiantly choosing to do her father’s will in a supreme act of selfless love”, stealing a few thoughts from Joseph Pearce of Ave Maria’s introduction, “not unlike our own Savior and His mom, and maybe we all here could learn a little from them about the beauty of obedience and fruits of self-sacrificial love.” And my hair would be perfect.

My fantasy ends with the bell ringing and me turning on my woolly heel and marching off to Mass, leaving behind a roomful of grateful converts.

I held the book in my arms. I supposed I couldn’t go back to class—the old gams just aren’t fit for stretch pants anymore--but I could read this book and begin my own re-education in the classics. Time to de-Uggly my B.A.

Copyright 2011 Meg Matenaer

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments