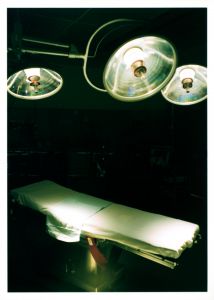

Having already endured three surgeries to repair my loose right shoulder, I grew increasingly more curious about what actually occurs behind those ominous operating room doors. My interest piqued even further when my left shoulder began to inexplicably loosen just as my right shoulder had done. Realizing I was facing yet another Capsulorrhaphy procedure which would stabilize my shoulder and keep it from popping out (as it often felt like it would at anytime day/night), gave me an even more vested interest in viewing an actual shoulder surgery repair.

Having already endured three surgeries to repair my loose right shoulder, I grew increasingly more curious about what actually occurs behind those ominous operating room doors. My interest piqued even further when my left shoulder began to inexplicably loosen just as my right shoulder had done. Realizing I was facing yet another Capsulorrhaphy procedure which would stabilize my shoulder and keep it from popping out (as it often felt like it would at anytime day/night), gave me an even more vested interest in viewing an actual shoulder surgery repair.

Good for me that I had a surgeon who was willing to let me both observe one of his actual cases (and write about it). As the date approached for viewing (which had to be cleared through a number of channels including the patient herself), I excitedly told friends and colleagues about my “opportunity” as I viewed it. Surprisingly to me, most people I talked to tried to warn me off, telling me I would never (ever) voluntarily agree to another surgical procedure having watched one so like my own. I wondered about this, then decided it was too good a chance to miss no matter what conclusions I came away with after the observation.

So with a little trepidation, I entered the very same hospital waiting room where I had sat for my previous three surgeries as a patient. This time was different though. Instead of getting prepped with a gown and an IV drip of various medicines, I was escorted back to the surgical desk area where I was given a temporary ID number so that I could retrieve my scrubs for the morning from a Scrubex machine. Interesting, that. I changed into a pair of nondescript green scrubs, put on a hair net and was handed a mask to wear. Being the non-astute medical garb wearer I am, I humbly accepted help on donning all three appropriately. So much for an auspicious start.

With a curt, “Follow me,” I was taken into the operating room right in step with the patient with whom I would observe and I noticed she was still awake and chatting comfortably with nurses and technicians. Standing as near as I could to watch what was being done, and with pen and paper in hand, I took copious notes for the next two hours. Transported, that’s what it felt like…to a completely foreign world where a team consisting of an anesthesiologist, a nurse anesthetist, the orthopedic surgeon, two certified surgical technicians, and a circulating nurse performed a marvelous dance of both precision and skill. I was amazed at how seamlessly every single clinical step meshed one to another. And how every person anticipated each other’s next move and responded in a well executed rhythm all under the surgeon’s expert guidance and specific instructions. It was an experience I won’t soon forget.

After this patient was put under a general anesthetic and then intubated, I watched closely as the surgeon made his incisions using the patient’s bony anatomy to keep his orientation. I looked on as a saline solution was injected into her injured shoulder to allow better visual clarity and to help ease the movement of the arthroscope (a pen sized instrument inserted into a joint through a 1/2 inch incision). The patient received pain medication injections (even though she was unconscious); and then several scopes were inserted at the beginning of the procedure (two of these the surgeon manipulated to perform the repairs while viewing a high definition TV monitor; the third was the camera which he moved around to seek out and inspect the damaged areas).

At various junctures, miscellaneous burring, whirring, trimming (think dental equipment) drill-like instruments were applied to the troublesome shoulder areas via the scope sites, each one serving its unique purpose in the tedious corrective procedure. After approximately two hours time, the surgeon had repaired this patient’s rotator cuff (using one screw (anchor) with three sutures); performed a SAD (Subacromial Decompression) which removed a bone spur from her shoulder blade; and did a Biceps Tenotomy (cutting the biceps tendon).

Once the surgery was completed (and the patient was sutured, cleaned up, and her newly repaired shoulder placed securely in a sling), I followed her to the Phase I recovery room (generally a 1-2 hour time period) where I learned even more about the risks and stresses of the surgery itself and how nurses carefully monitor each individual as they begin to awaken from anesthesia. The nurse attending to this still semi-unconscious patient explained the precautions taken to ensure every individual under medical care is prepared to make a full recovery.

When the patient was alert and met all the vital sign criteria, she was moved to Phase II recovery where her family rejoined her. Here, a different team of nurses answered release questions, prepared her discharge papers and offered miscellaneous creature comforts. For this particular patient, she was released to go directly home. For others, some are kept in hospital overnight or longer depending upon extenuating circumstances or their special health requirements.

On this spring morning, in this particular hospital, in just one surgical operating room, I was initiated into a world of clinical terms, medical phraseology, and complex technical procedures I had only imagined before. Perhaps the most significant takeaway I learned from my morning in the OR was that for the individuals who make this their workplace, there is no decision or movement deemed insignificant. Each of the minutest paces these medical professionals put themselves through is done with a specific purpose in mind: to ensure the safety and the healing of their patient. Humbled and honestly overwhelmed, I recognized how helpful it would be if all laypeople could witness some type of surgical procedure in order to fully appreciate the expertise of the men and women behind their ultimate physical recovery.

Changing back into my own clothing, I deposited my scrubs into the Scrubex machine for cleaning whereupon I was given “7” credits for the return. I’d like to believe I’ve come away with far more than a mere credit to my account. No doubts on that score, I know I have.

ON A NEED TO KNOW BASIS: WHAT EVERY PATIENT NEEDS TO KNOW

Dr. Christopher A. Foetisch, orthopedic surgeon at the Toledo Clinic, Toledo, OH, offers the following pre-surgical preparation recommendations. Note how the most effective pre-surgical steps women can take encompass readying both the mind and body.

BODY FACTS TO CONSIDER BEFORE SURGERY: Information to Heal Strong

- Stress, depression and anxiety prior to surgery have all been linked to poor recovery after surgery. Note also that elevated levels of cortisol; the body's primary stress hormone, negatively affects wound healing. High cortisol levels dampen the immune response. As a result, this imbalance can delay healing while increasing the risk for wound problems such as post-surgical infections.

- Any surgical procedure places an increased demand on the body. As a result, protein and calorie needs are increased 20-50% over normal requirements. Without enough dietary protein, the body must break down muscle and organ tissue that can impair the immune system and deplete energy and strength needed for recovery.

- Exercise has a clearly demonstrated a positive effect on surgical outcomes. According to a 2005 report from the Journal of Gerontology, wound healing is 25% faster in those patients that exercised three weeks prior to surgery compared to those who maintained their normal routine. Additionally, exercise improves circulation and strength that lead to increased mobility after surgery.

HOW WE THINK: Making Your Mental Expectations Work for You

- Individuals need to embrace a "can do" attitude. Those patients who are invested in their own recovery, typically do extremely well relative to those who are apprehensive or anxious prior to surgery.

- The power of positive thinking does go a long way. Most often, if an individual thinks she will do well, she does. Flipside, when a person anticipates struggling or frets about experiencing potential problems after surgery; that individual’s recovery will be much tougher.

- Adopt reasonable expectations. Getting well takes time and patients must be willing to commit both emotionally and physically to the recovery process to create the best environment for healing strong.

WHAT TO DO: Simple Measures to Positive Results

- Make sure to eat a balanced diet that has adequate protein intake.

- Exercise for a minimum of three weeks prior to surgery.

- Avoid pre-surgical stress and anxiety or consider delaying an elective procedure until the intense season has passed or can be more easily managed.

- Ask yourself self-check questions regarding your overall attitude toward the surgical procedure and your willingness to be fully committed to the recovery process.

Copyright 2012 Michele Howe

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments