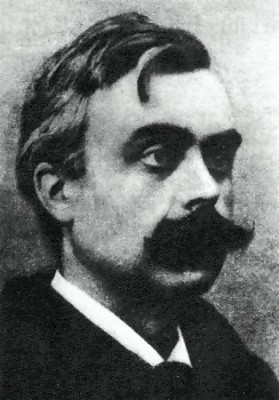

I recently came across a phrase written by 20th century Catholic French novelist Léon Bloy: “The worst evil is not to commit crimes but to have failed to do the good one might have done.” For Bloy, these words were shaped by the looming human catastrophe of World War I, and haunted him deeply as he considered his vocation as a writer of “the Absolute.”

Bloy wanted to be “a saint and a worker of miracles,” notes Robert Ellsberg in his profile of Léon Bloy in “All Saints.” Instead, Bloy became “a man of letters.”

Vocationally we find in Bloy’s life two important dimensions of discerning God’s willing which occur in our own lives as well. First, he writes of that larger vocational arc in the life of the baptized Christian: “the good one might do,” indeed, the good one has been sacramentally anointed to do—and the moral failure when we back away from, or even actively resist acknowledging, the graced invitation to live our anointed life wholeheartedly.

Second, Bloy feels dismay that he has not followed the path of holiness that would enable him to “become a saint and a worker of miracles.” Rather, he has become merely “a man of letters,” a writer. His picture of “a saint and worker of miracles” was different from what God imagined.

But here’s the backstory: Through Bloy’s writing on the Absolute and the mystery of God in the midst of human suffering, two young French intellectuals—Jacques and Raïssa Maritain—ended their search for Truth when they discovered, through Bloy’s writings, the Catholic faith, and asked him to be their sponsor at baptism. (Young Jacques and Raïssa had vowed to commit suicide if they could not find Truth within one year. So driven were they in their search that they would even consider “going to the dunghill,” the Catholic Church, in search of it.)

Because Léon Bloy was faithful to God’s calling, two lives were set in motion in the Holy Spirit. Jacques Maritain later became a key contributor to the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights which captures core elements of Catholic social teaching.

What’s the takeaway here? Your sacramental anointing to be “a saint and worker of miracles” might look far different from what you imagine, far more immediate and engaged in the grit of life. The inequities and suffering of our time can easily lead to interior numbness and apathy. Vocationally we struggle with the unwanted challenge to hold the world’s anguish in our hearts and to make it the matter of our prayer. Early 20th century French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who, as a priest on the battlefield had no host for consecration, took the war-torn world and made it the matter of his offering.

God continually invites us to wake up to our calling. The world’s anguish isn’t just daily news feed. It is God’s constant invitation to us to achieve our full vocational stature. Vocationally we are stewards of the world’s condition, commissioned to press for justice and stand as an unbroken circle of compassion, defending human dignity among those who are most oppressed. Our work is to make of today’s atrocious human suffering an offering to God. This is our priestly work for the sake of the world.

How can we do this work in a worthy manner? How does God desire to express justice, compassion, and hope through you, through me? How do we become the saints and workers of miracles God has in mind? Our priestly work is to stand in the gap between the world’s anguish and God’s mercy, and to resist structures of greed and oppression with the power of Christ’s resurrection.

The world itself is crying out for us to do the good which God has in mind, the urgent good which will make us “saints and workers of miracles” according to God’s design, not our own.

Copyright 2013 Mary Sharon Moore, M.T.S.

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments