Some say that a religious perspective shapes one's creativity to such an extent that it corrupts art for its purposes. But does a non-religious perspective act in the same way? Does a non-religious perspective also corrupt art for its purposes?

Some say that a religious perspective shapes one's creativity to such an extent that it corrupts art for its purposes. But does a non-religious perspective act in the same way? Does a non-religious perspective also corrupt art for its purposes?

A myriad of perspectives abound in our world: how do we see the world around us, how do we choose to live in it? A writer’s beliefs, whether religious, political, or social, will affect his or her creation. It is a matter of degree whether the creation becomes art, or whether it is turned into propaganda, which is not art.

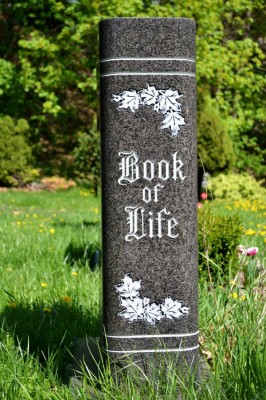

Religion does not compromise art, and is not an impediment to the fiction writer. On the contrary, it aids in creativity, providing a component that pushes life and human reason to a higher, non-material level than simple, day to day dogmatisms. It is a lens through which an author translates a very human world, without moralizing propaganda, but rather with an empathy for all that makes us human, both spiritual (invisible) and physical (visible) components.

A common experience to humanity is one of depravity. The Christian author’s lens is the grace of God offered to humanity in spite of its depravity, but the reader shouldn’t have to be a believer to appreciate the author’s story.

Some Christian authors write a story that is slavishly and artificially constructed to argue his point. The story is not nearly as important as the moral of the story. This may, at first, sound logical. But this is definitely not the right approach to writing fiction—for Catholics or anyone.

Here is Flannery O’Connor’s Catholic orientation: from the sign to the thing signified, from the visible to the invisible, from the sacrament to the mystery. The more real fiction is, the more the story confronts the reader with concrete details in the language rather than abstract ideas, the greater and more forceful the metaphysical persuasiveness and power.

Readers of “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” for example, are not subjected to a Catholic lecture on human sinfulness; rather, “The Misfit” as a character is so concretely and vividly and authentically presented to our senses that we know him intimately, and the wickedness in his heart and life—and ours?—is a reality that cannot be denied without great effort.

Flannery O’Connor, as a Catholic Southern writer, understood that fiction is not firstly and ultimately about an idea, but about incarnation. It is about the concrete. It is about matter. It is about life. And this is the Art of Christian Fiction.

Based on Flannery O'Connor's Religion and Literature:Dogma and its Implications for Art, by Tami England Flaum:

[embed]http://youtu.be/oW6vx5AOMqM[/embed]

Copyright 2014, Kaye Hinckley

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments