One of the biggest surprises my all-too-naive self had upon getting married was discovering that sex was a lot less like that one scene from Somewhere in Time and a lot more like what I once saw two zebras doing at the zoo.

No offense, zebras. (Photo by Paul Maritz, available from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zebra_Botswana_edit02.jpg)

No offense, zebras. (Photo by Paul Maritz, available from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zebra_Botswana_edit02.jpg)

I’ll admit, despite the awesomeness of finally being able to “do it,” I was actually somewhat disappointed to discover that sex was often awkward, messy, painful, and/or downright ordinary, even months and years beyond the honeymoon. Many a “good Catholic” chastity talk (especially the kind found in my generation) and romantic movie had given me the impression that such a sacred act would by nature feel sacred--or perhaps, more accurately, fit my personal concept of sacred--in every regard and at all times.

I guess I don’t know what I really expected. Something a little more graceful comes to mind, and certainly without the need to clean up anything but rose petals.

Don’t get me wrong, I like sex. I like it a lot. I think my husband is good at it. I just had no idea how un-holy it would seem at times.

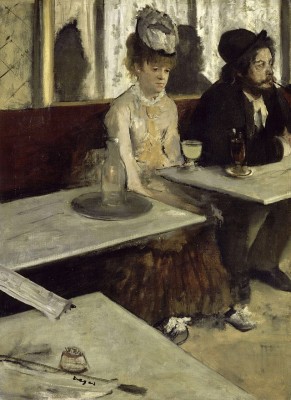

One of my favorite paintings of raw, un-holy feeling, human experience. ("L'Absinthe" by Edgar Degas)

One of my favorite paintings of raw, un-holy feeling, human experience. ("L'Absinthe" by Edgar Degas)

I credit this to my adoption, in at least some part, of a very flawed but common Christian ideology, in which what is good, true, and beautiful is only what is graceful, clean, good-feeling, and/or extraordinary.

Prior to getting married and having children, I would have sworn I took no part in such an ideology. However, the nature of being married and having children have proven time and time again to me, through my under-appreciation and sometimes outright abhorrence for what is awkward, messy, painful, and/or ordinary, the little flakes of this mistaken mind-set that continue to infiltrate my thinking.

But as I mentioned, this ideology is common and even saturates parts of the Christian world. Consequently, whatever doesn't fit the flawed schema of what is sacred is often denied its full weight, its glory, in the human experience.

For example, take the "message art" that Simcha Fisher describes here. Its existence implies that, to at least some degree, real art, devoid of an explicit "Jesus saves" message and rife with human nature, is somehow perceived as less worthy in many subsects of Christianity.

This concept of holiness and worthiness is not only completely irrelevant to a post-modern mankind steeped in the awkward, messy, painful, and ordinary realities of life, but it’s not Christ-like.

Section 22 of Gaudiem et Spes explains how God, by his incarnation, embraces and redeems human nature in its fullness:

“Since human nature as He assumed it was not annulled, by that very fact it has been raised up to a divine dignity in our respect too. For by His incarnation the Son of God has united Himself in some fashion with every man. He worked with human hands, He thought with a human mind, acted by human choice and loved with a human heart. Born of the Virgin Mary, He has truly been made one of us, like us in all things except sin.”

Humanity, though already beautiful in being a creation of God, becomes even more beautiful, more glorious because God chose to become human himself. Because of the Incarnation, the awkward, messy, painful, and ordinary realities of human life need not be treated with contempt and denial:

Sex does not have to end in euphoric pleasure followed by worship hymns to be holy. Tears may be cried and sorrow felt completely without worry that such feelings are “unbecoming” of a good Christian who is aware of the resurrection. One can fill their day with ordinary work without any explicitly Christian message attached to it and still be living a truly sanctified and beautiful life.

"Christ was born to raise up the likeness that had fallen," the season's prayer tells us, the likeness with which we were originally created and lost to sin. "Eden has been opened to all," because Christ has come to heal our sinfulness.

This is a Christianity that can change lives and enlighten hearts because it can embrace the entirety of human existence, even to the point of embracing and healing--not just covering, but truly healing--sin.

This is a Christianity that shows us how those awkward, messy, painful, and ordinary realities can be part of the abundance of abundant life, rather than a distraction from it.

This is a Christianity that calls us to be what we are yearning to be at every moment: human. Created in the image and likeness of God, yes, but still completely and totally human.

What does this mean for us? How do we embrace our humanity created in the image of God and still work to regain our God-likeness?

I think the prayer, fasting, and almsgiving of our Philip’s Fast provides a decent first step, especially as it intensifies in these last days leading up to the Nativity. We can pray for the Holy Spirit to enlighten us and teach us to be better, more fully human beings. (The Emmanuel Moleben is a traditional prayer for the fast and may be a good place to start.)

We can fast to reform our passions as well as to gain a better understanding of how our fallen human likeness continues to need God’s healing. We can perform acts of compassion specifically aimed toward becoming “incarnate” to those around us by sharing in the awkward, messy, painful, and ordinary realities of their lives and drawing one another closer to Christ through our love.

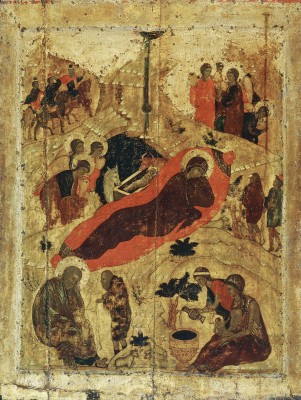

And then when Christmas finally comes, filled as it is with some of the most awkward, messy, painful, and ordinary moments of human existence, we can celebrate an incarnate God born to give unity to humanity and divinity:

"God is now on earth, and man in heaven; on every side all things commingle. He became Flesh. He did not become God. He was God. Wherefore He became flesh, so that He Whom heaven did not contain, a manger would this day receive. He was placed in a manger, so that He, by whom all things are nourished, may receive an infant's food from His Virgin Mother. So, the Father of all ages, as an infant at the breast, nestles in the virginal arms, that the Magi may more easily see Him. Since this day the Magi, too, have come, and made a beginning of withstanding tyranny; and the heavens give glory, as the Lord is revealed by a star.

To Him, then, Who out of confusion has wrought a clear path, to Christ, to the Father, and to the Holy Spirit, we offer all praise, now and forever. Amen."

Copyright Brittany Balke, 2014

About the Author

Guest

We welcome guest contributors who graciously volunteer their writing for our readers. Please support our guest writers by visiting their sites, purchasing their work, and leaving comments to thank them for sharing their gifts here on CatholicMom.com. To inquire about serving as a guest contributor, contact editor@CatholicMom.com.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments