Rebecca W. Martin discusses three ways carefully-chosen fiction can help parents guide their growing children into adulthood.

When I was a child, I used to talk as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a man, I put aside childish things. (1 Cor. 13:11)

There comes a point in life when adulthood beckons, and of course it’s up to the parent to guide that change. But good fiction can support your efforts, using examples of other children and other circumstances to round out your and your child’s personal experiences.

Truth be told, pretty much every piece of middle-grade or young adult fiction contains some elements of the coming-of- age story. As they should! Those are the years when children start to ask the questions that matter, and they need answers. Who am I? Who am I meant to be? How do I become that person?

It’s up to us to make sure that the stories our children read will guide them to the truth: Who am I? A beloved child of God. Who am I meant to be? A virtuous man or woman capable of loving Him and others; ultimately, a saint. How do I become that person? By learning, striving, repenting, and growing in relationship with those around me.

So how do we identify a good coming-of-age story — one that leads the young reader closer to the true answers to their questions? Let’s dive in.

Is the family around the main character modeling the values and virtues you want your child to pick up?

Humans are meant to live in community, and an essential preparation for adulthood is discovering just how to do that. A coming of age story usually addresses this through the role of the family. Whether we’re reading about a found family, a broken family, a Christian family, or a secular family, the important question is whether your child is going to take away from this fictional family the values and virtues necessary for life in community.

Who does the main character look up to? What is this mentor teaching?

Humans are intrinsically conformative creatures—we imitate the people around us, without even realizing that we’re doing it. And imitation is a valuable tool to shape a children’s character. In most coming-of-age stories, the young protagonist is influenced by a specific adult, whether a parent or another adult outside of the family. The words and actions of that mentor figure tell you most of what you need to know about what your child is going to take away from the story. Is that mentor giving an example of a well-formed, virtuous adult? If so, your child will be equipped to find similar mentors in real life, and that imitative tendency can become a path to virtue.

What is the coming-of-age moment? What does the main character take away from that moment?

Through the influences of the family and the adult mentor, the child moves towards the climax of the story, the coming-of-age moment. This transition may take place in different ways: as the result of a traumatic or inspiring experience, an ultimate realization of some truth about adulthood, or a final acceptance of the inevitable change. But the content and takeaway of this scene will always illustrate the fundamental message of the book. It’s for you to decide whether that message is the one you want your children to absorb.

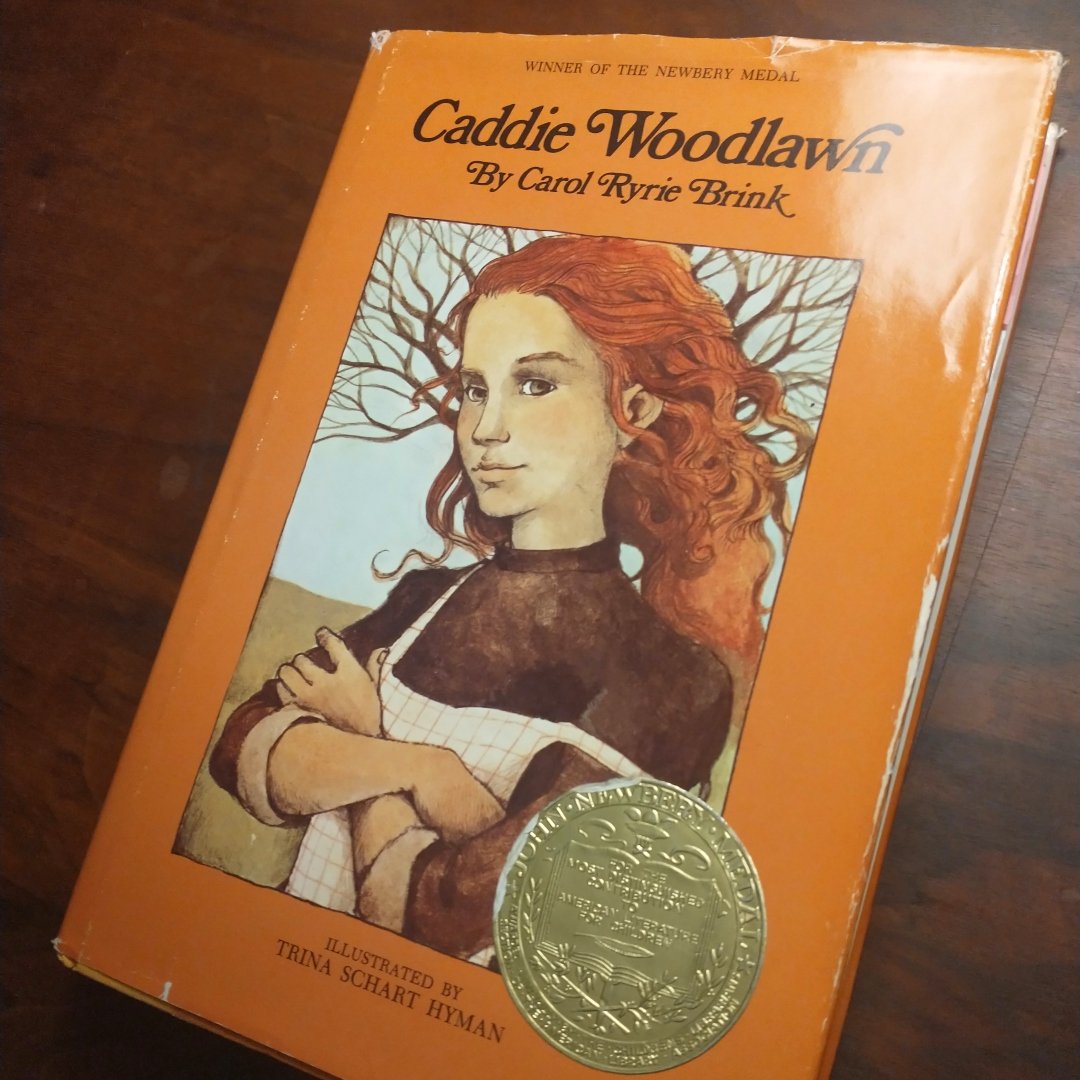

The best way to explain this, and to put these three questions together, is to look at one of my all-time favorite books: Caddie Woodlawn, by Carol Ryrie Brink. It’s the story of a Civil War-era Wisconsin girl who begins the book as a wild young tomboy, a lifestyle encouraged by her father’s desire for a strong, healthy daughter. Caddie sees her “ladylike” mother, sister, and cousin as restricted and stifled, and looks to her father as her model instead. As Caddie feels adulthood approaching, she flails against her understanding of what it means to be a woman. Eventually, she indulges in a mean prank against her prim and proper cousin, and is punished for her behavior.

The candid conversation which follows between Caddie and her father is the turning point of the book. Mr. Woodlawn invites his daughter to a life worth living:

“A woman’s work is something fine and noble to grow up to, and it is just as important as a man’s. But no man could ever do it so well. I don’t want you to be the silly, affected person with fine clothes and manners whom folks sometimes may call a lady. No, that is not what I want for you, my little girl. I want you to be a woman with a wise and understanding heart, healthy in body and honest in mind. Do you think you would like to be growing up into that woman now? How about it, Caddie, have we run with the colts long enough?”

Caddie responds to the call, and by the end of the book, reflects on the change that has been brought about in her.

“What a lot has happened since last year when I dropped the nuts all over the dining-room floor. How far I’ve come! I’m the same girl and yet not the same. I wonder if it’s always like that? Folks keep growing from one person into another all their lives, and life is just a lot of everyday adventures. Well, whatever life is, I like it.”

And isn’t that what we want for all of our children: that one day they can say, “Look how far I’ve come!”

Copyright 2023 Rebecca W. Martin

Images: (from top) Canva; Canva; copyright 2023 Rebecca W. Martin, all rights reserved; Canva

About the Author

Rebecca W. Martin

Rebecca W. Martin, a trade book Acquisitions Editor for Our Sunday Visitor and Assistant Editor at Chrism Press, lives in Michigan with her husband and too many cats. A perpetually professed Lay Dominican, Rebecca serves as editor for Veritas, a quarterly Lay Dominican publication. Her children’s book Meet Sister Mary Margaret will release in fall 2023 from OSV Kids.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments