I am a member of Generation X. For those of you who don’t remember, we were the ones who wore our skin-tight swan-emblazoned Gloria Vanderbilts and polyester pink “satin” blouses to the school dance, kicked off our stiletto mules in a pile at the door, and danced in our ankle socks. We bounced up and down to the driving beat of a song you probably, thankfully, have never heard called My Sharona. (I am guessing the school administration never bothered to listen to the lyrics to that one. Believe me when I say you don’t want to either.)

Sometimes the little bows on our shoulders, gathering our sleeves into bunchy ruffles, would come untied mid-song, and we would have to contort one of our hands into unnatural configurations to aid the other in re-tying it. We would have to do this discreetly, mind you, because although we were wearing all those flashy clothes and making our bodies move in all those unexpected ways, we did not want anyone looking at us.

Then would come the slow dance—Reunited or Sad Eyes—and the dance floor would clear, and our backs would take their places against the wall, and we would hope for an invitation, which only ever came from the boy who was a full head shorter than we were: that fearless, unappreciated, underrated, much-maligned boy, who was actually putting into practice all that our generation professed to believe.

The meaning of life back then was to seek self fulfillment. It was to find happiness by finding whatever makes you happy and never give up or give in or give out until you achieved, attained, or acquired it. I remember all the poems and songs we amateur poets and songwriters put down on paper. Oh yes, we were deep thinkers back then, those of us who held guitars in our hands. Not, of course, those who held pom-poms or Homecoming scepters. No the “deep” thinking came from those of us who stayed in our rooms and scratched out lyric after lyric, all of which had a supposedly “fresh” delivery of the same message: follow your dreams.

Then we grew up.

At some point in our running toward the goal of gratification, we heard another voice. It said this:

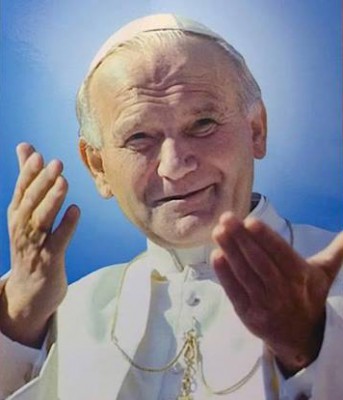

“I plead with you—never, ever give up on hope, never doubt, never tire, and never become discouraged. Be not afraid.”

You know whose voice that was. It was the voice of a man who knew who we were and loved us anyway. He spoke our language, used our words. But he laced them with something entirely revolutionary that we could only fully understand after something substantial within us changed.

A number of months ago, during a radio interview, I made the statement that fear is at the root of every abortion. I said that people abort their children with Down syndrome because they are afraid.

When EWTN radio host Al Kresta asked me why my husband and I were not afraid to adopt our daughter Teresa, who has Down syndrome, I had to tell him that wasn’t the case.

I am afraid of everything. Afraid of loss. Afraid of humiliation. Afraid of germs and high places and typos. Afraid of getting caught in rush hour traffic. Afraid that the egg yolk will dry on the plate before I have a chance to rinse it. Afraid of choosing the wrong grocery checkout line. Afraid of losing too much sleep, eating too much fat, getting too many gray hairs. Afraid of running out of coffee. And the big one: afraid of screwing up something really important.

So when the adoption case worker calls and asks if we will adopt a child with drug exposure or Down syndrome or 15-week prematurity and seventy percent chance of Cerebral Palsy, why should I say yes?

There was fear involved in all our adoptions, I told Kresta, but that didn’t much matter. I try to base all my decisions on love, not fear. I wonder if I would have ever conceived of such a method of decision making were it not for those words, echoed in a Polish accent throughout my generation: Be not afraid.

At some point, if we were to become a triumphant generation, we would have to recognize fear for what it is: an ugly tyrant that seeks to destroy every good that ever could be done. John Paul II showed us another way. “Genuine love is demanding,” he told us. “But its beauty lies precisely in the demands it makes.”

Like many people with Down syndrome, my 11-year-old Teresa struggles with speech. She has a limited vocabulary and can only pronounce certain words, so she chooses the ones that get her point across most efficiently and with the most impact. She has been calling John Paul II “Pope Saint” for years, ever since we visited a travelling John Paul II museum.

I am sure last month’s Canonization was no surprise to her, since she had the man pegged long ago. She mentions “Pope Saint” in her prayers every night, and I get the honor of witnessing that special connection between the two of them and the comfort of knowing that the man who revolutionized the concept of hope for the “deep thinkers” of my generation still speaks to the simplest of hearts in the next. It’s something I never would have witnessed had I not known it was possible to be freed from the tyranny of fear. I never would have known Teresa had I not known the words of our Lord, lived and spoken by John Paul II.

Be not afraid.

We could argue all day long and well into the night about the most important contribution St. John Paul the Great made to the world. There are so many. But you will be hard-pressed to prove any could be more profound than the ripple effect of hope that seemed to flow so naturally from the man who taught us that the only thing to fear is the possibility that we might love too little.

Copyright 2014, Sherry Boas

About the Author

Sherry Boas

Sherry Boas is author of the Lily Series, which has grown into a beloved collection of novels whose characters’ lives are unpredictably transformed by a woman with Down syndrome. The former newspaper reporter and special needs adoptive mother of four is also author of A Mother's Bouquet: Rosary Meditations for Moms, Billowtail, Victoria's Sparrows, Little Maximus Myers, Archangela's Horse, and Wing Tip. She runs Caritas Press from her home office in stolen moments between over-cooking the pasta and forgetting to dust the chandelier. Find her work at CaritasPress.org.

.png?width=1806&height=731&name=CatholicMom_hcfm_logo1_pos_871c_2728c%20(002).png)

Comments